Alessandro Scarabello

06.12.2012 – 09.02.2013

Exhibition view

installation view at The Gallery Apart Rome, 2012

installation view at The Gallery Apart Rome, 2012

installation view at The Gallery Apart Rome, 2012

installation view at The Gallery Apart Rome, 2012

Works

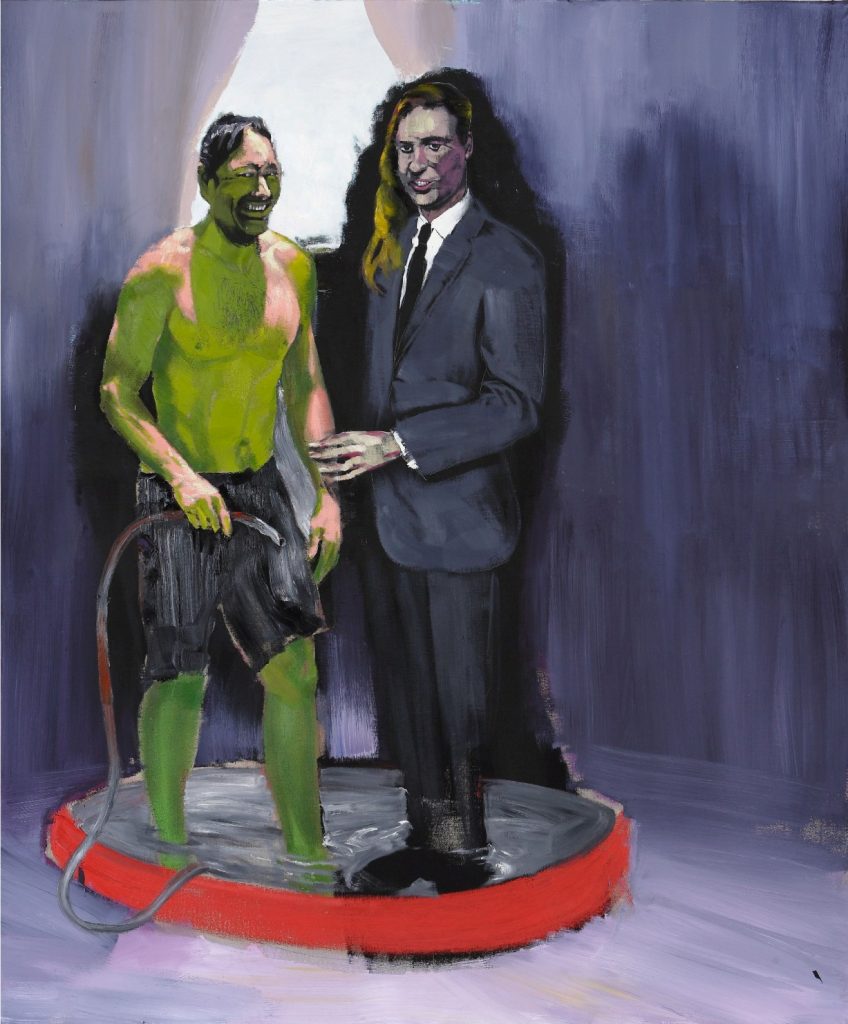

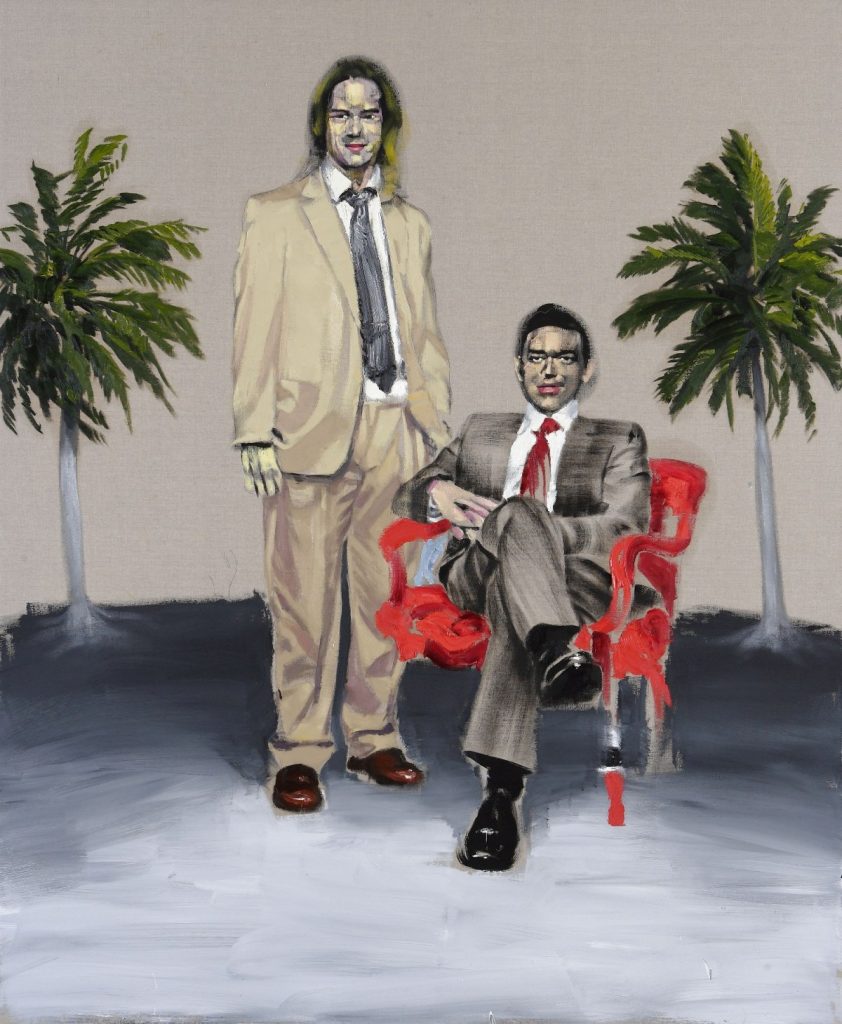

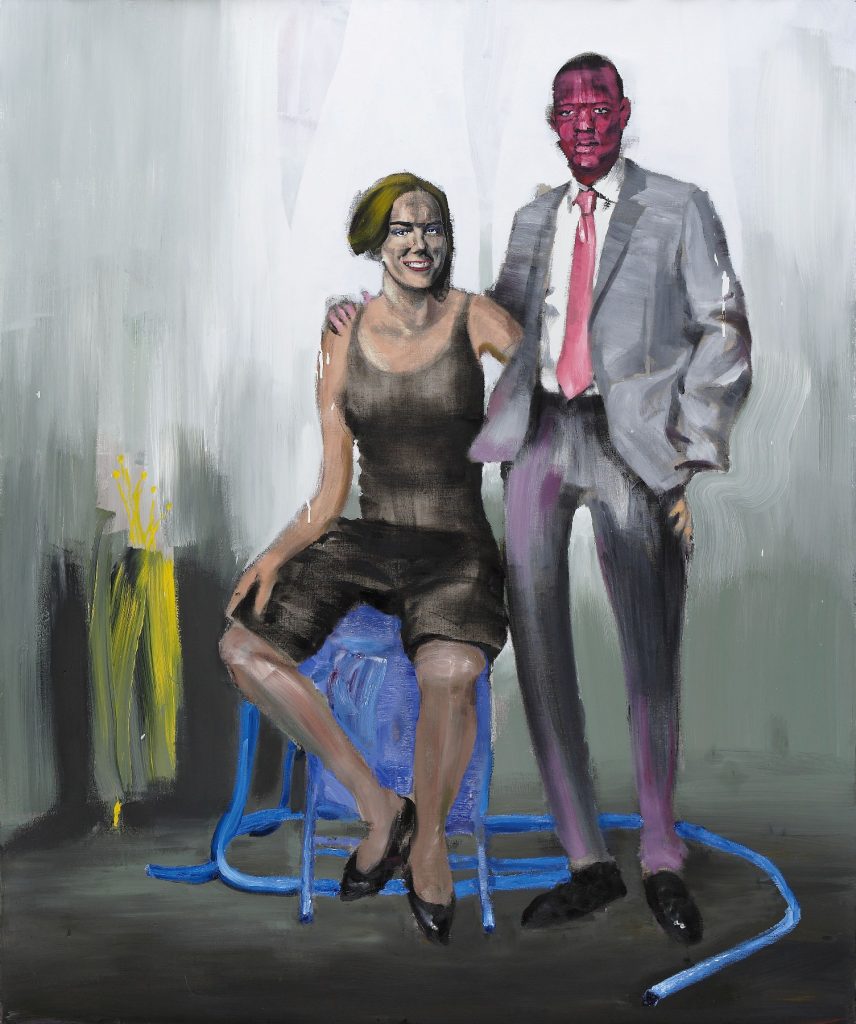

Uppercrust #1, 2011, acrilico e olio su tela cm187x154

Uppercrust #2, 2011, acrilico e olio su tela cm187x154

Uppercrust #3, 2011, acrilico e olio su tela cm187x154

Uppercrust #7, 2011, acrilico e olio su tela cm187x154

Uppercrust #8, 2011, acrilico e olio su tela cm187x154

Uppercrust #9, 2011, acrilico e olio su tela cm187x154

Uppercrust_heads #11, 2012, acrylic and oil on canvas, cm 29 x 31

Uppercrust_heads #20, 2012, acrylic and oil on canvas, cm 29 x 31

Uppercrust_heads #68, 2012, acrylic and oil on canvas, cm 29 x 31

Uppercrust_heads #75, 2012, acrylic and oil on canvas, cm 29 x 31

The Gallery Apart is proud to present Uppercrust, Alessandro Scarabello’s latest series of paintings and his third solo exhibition at the gallery.

“Upper crust” is an expression used in Anglo-Saxon societies to describe members of the highest social classes, the new aristocracy that exploits its dominant position in economic and financial terms, as well as in communications, in order to influence the masses. The phrase refers to loaves of bread baked in the ovens of the manor houses of the past that were perfectly brown on top (the upper crust) and burnt on the bottom. The top was set aside for the master of the house, while the bottom was designated to the servants. Through this expression, Scarabello continues his examination into humanity, looking at the protest movements that spread across the world over the past few years of the economic crisis and the renewed awareness of that 99% of the world population that has to bow down daily to the rules, the power and the interests of the remaining 1% of humanity. And it is this 1% that becomes the subject of his research. Thus, Scarabello gives life to the Uppercrust series, twelve large paintings, four of which are on exhibit in the gallery. They are life-size portraits of women and men, through whom the artist conveys the presumptuous confidence of belonging to an elite that looks down on the rest of the world from high above – and which the rest of the world looks up at with envy and contempt, but also with an ill-concealed desire of sharing its status.

Scarabello examines power through the portrayal of those who hold it and looks at the effects that the execution of power has on the protagonists’ faces, bodies, postures and attitudes. His portraits, intentionally far from the true-to-life photographic models and the result of a free flowing expression of the artist’s imagination and own unique inner vision, delve into what Scarabello defines as the raw naked soul. They also aim to convey to the beholder a feeling that evokes the sense of superiority of those who are portrayed and who appear aware of their roles as representatives of an elite community. And precisely in order to highlight this community aspect, this ability to not waste energy in the defense of individual privileges, Scarabello chose to position three large standing paintings in a triangular formation, hinged together on their sides allowing the structure to stay upright – exactly like the relationships, bonds and alliances that prop up the elites and allow their members to support each other. Similarly, a fourth painting appears free-standing in the middle of the space, yet it conceals a slender wood structure that sustains it. Thus Scarabello introduces the concept of weakness – a feebleness in substance that often hides behind common displays of power. Here he is inspired by the Potemkin village myth in which hollow facades of towns were constructed in order to impress the Empress Catherine II during her visit to the territories which had been annexed from the Ottoman Empire.

It is a physical representation of force that, however, hides the emptiness that lies behind it. Thus Scarabello introduces the concept of weakness which is present in the real substance of power. Here the artist is inspired by the Potemkin village myth in which hollow facades of towns were constructed in order to impress the Empress Catherine II during her visit to the territories which had been annexed from the Ottoman Empire.

In addition to the large life-size paintings, Scarabello exhibits smaller works, some of which are framed and others which are not, on the walls of the gallery. The paintings are a selection from a large series of more than one hundred portraits which make up a sort of catalogue of the different types of human beings who give life and breath to the meaning of power. Among these is a portrait of a figure that is half man and half cat. Also here, Scarabello recalls the Anglo Saxon tradition in which felines are a badge of aristocracy. It is a symbolic image that, more than others, joins pictorial realism, which Scarabello uses as an anchor, to daily life and oneiric imaginariness – which are indispensable to the artist in digging through the visible reality and reaching the raw state of the soul. It is for this reason that Scarabello duplicates the symbol-image in a photographic version that becomes a sort of graffiti, hidden, as a real cat would, in one of the corners of the gallery.

The Gallery Apart è orgogliosa di presentare Uppercrust, l’ultimo ciclo pittorico di Alessandro Scarabello, alla sua terza personale in galleria.

“Upper crust” è l’espressione con cui nelle società anglosassoni vengono indicati gli appartenenti alle leading classes, la nuova aristocrazia che utilizza la propria posizione dominante in termini economici, finanziari, di comunicazione e quant’altro per influenzare le masse. L’espressione richiama le forme di pane che un tempo venivano cotte nelle cucine delle dimore nobiliari e che inevitabilmente presentavano un livello di cottura perfetto nella parte alta (uppercrust, appunto), destinata ai padroni, mentre la parte sottostante bruciata serviva a sfamare la servitù. Scarabello prosegue quindi la sua indagine sull’umanità, prende spunto dai movimenti di protesta diffusisi nel mondo durante questi anni di crisi e dalla rinnovata consapevolezza di chi fa parte di quel 99 per cento di persone che quotidianamente devono piegarsi alle regole, al potere e agli interessi del restante 1 per cento dell’umanità. Ed è proprio questo 1 per cento che diventa oggetto della sua ricerca. Scarabello crea così la serie Uppercrust, dodici grandi tele di cui quattro vengono esposte nella mostra in galleria. Sono ritratti di donne e uomini dipinti a grandezza naturale, di cui l’artista ci rende tutta l’altezzosa consapevolezza di appartenere ad una élite che può guardare il mondo dall’alto verso il basso e a cui il resto dell’umanità guarda con invidia e disprezzo ma anche con malcelata voglia di condivisione.

Scarabello indaga il potere attraverso la rappresentazione di chi lo detiene e scandaglia gli effetti dell’esercizio del potere sui volti, sui corpi, sulle posture e sugli atteggiamenti dei protagonisti. I suoi ritratti volutamente lontani da realistici modelli fotografici e frutto invece del libero flusso della fantasia e delle visioni interiori dell’artista, scavano in quello che Scarabello definisce lo stato crudo dell’anima e tendono a rendere allo spettatore un’emozione in grado di evocare il senso di superiorità di chi, ritratto nel dipinto, sembra quasi consapevole del ruolo di rappresentante di una comunità elitaria. Ed è proprio per sottolineare questo aspetto comunitario, questa capacità di non disperdere le energie necessarie per la difesa delle proprie prerogative, che Scarabello ha immaginato di allestire tre grandi tele posizionandole a parallelepipedo, unite da cardini che consentono alla struttura di tenersi eretta, esattamente come legami, convergenze, alleanze sorreggono le élites e consentono ai loro membri di sostenersi l’un l’altro. È una rappresentazione plastica di forza che però nasconde il vuoto retrostante, introducendo così anche un’idea di debolezza circa la reale sostanza del potere; qui Scarabello rimanda ai Villaggi Potemkin costruiti in cartapesta per impressionare l’imperatrice Caterina II in visita ai territori sottratti all’Impero Ottomano. Oltre alle grandi tele a dimensione naturale, Scarabello presenta alcune piccole tele, in parte intelaiate e in parte no, disposte a parete; è una selezione di una ampia serie di oltre cento ritratti costituenti una sorta di catalogazione dei tipi umani che danno carne e vita al potere. Tra loro il ritratto di un uomo gatto, anche in questo caso un rimando alla tradizione anglosassone dove il gatto è simbolo di aristocrazia, un’immagine simbolica che meglio di altre coniuga il realismo pittorico che Scarabello utilizza quale ancoraggio alla quotidianità vissuta e un immaginario onirico indispensabile all’artista per scavare oltre la realtà visibile e raggiungere lo stato crudo dell’anima. Ecco allora che Scarabello duplica l’immagine simbolo in una versione fotografica che diventa una sorta di graffito nascosto in uno degli angoli della galleria, esattamente come farebbe un gatto.

share on